|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gallery | People | David Starr Jordan

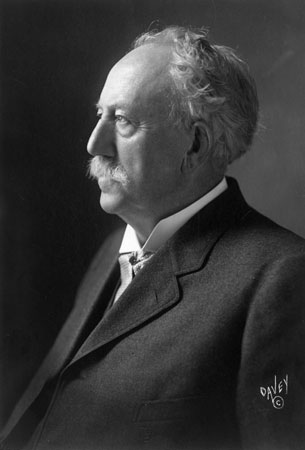

David Starr Jordan

"Go to the University of Indiana; there you will find the president, an old student of mine, David Starr Jordan, one of the leading scientific men of the country, possessed of a most charming power of literary expression, with a remarkable ability in organization and blessed with good sound sense. Call him." This was the advice that President Andrew D. White of Cornell gave to the Stanfords, who earlier had tried to recruit him as the university's first president. That same evening the Stanfords headed their private railroad car for Bloomington.

"My first impressions of Leland Stanford were extremely favorable, for even on such slight acquaintance he revealed an unusually attractive personality," Dr. Jordan wrote. "His errand he explained directly and clearly.... His education ideas, it appeared, corresponded very closely with my own." Dr. Jordan went home to discuss the offer with his wife. They were intrigued by the possibilities of a new university with a new academic plan in a pioneer state and decided that same day, just six months before the university opened, to accept. "The possibilities were so challenging to one of my temperament that I could not decline," he said. For his part, Stanford told a reporter back in California, "I might have found a more famous educator, but I desired a comparatively young man who would grow up with the University." Jordan, a renowned ichthyologist, was 40 when he took the position as first President of the new Leland Stanford Junior University.

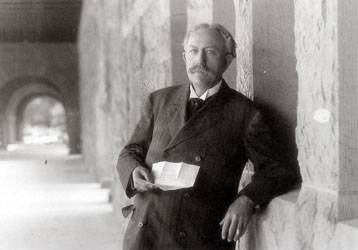

David Starr Jordan after he became Stanford University's first President. Stanford Archives. |

Afte Leland's death, Jane Stanford was deeply involved in university affairs and was driven to complete the physical campus she and her husband had envisioned. Her focus on building limited the resources available to President David Starr Jordan for expanding the academic program. It was during this period he bemoaned the fact that academic budgets were being held in check in order to finance "Stanford's Second Stone Age." He and the faculty looked forward to the end of construction and a greater financial commitment to academic pursuits. In June 1903, Jane transferred control of the university’s endowment to the Board of Trustees, and she urged the board to increase graduate enrollment and support research and teaching. However, it was only with her death in February 1905 in Honolulu that the transfer of powers was legalized, and funds continued to flow to the construction of several significant buildings through 1905.

As the 1905-06 academic year began, the direction and success of the university rested with the Board of Trustees, President Jordan, and the faculty, students, and alumni. Initial growing pains appeared to be behind them and the future looked promising. 1,603 students were enrolled in the fall term; 176 professors, instructors, and teaching assistants were listed on the payroll; the library counted 85,928 volumes in its collection; and the alumni association was vibrant. Jordan’s plans for educational expansion were in place. The earthquake of April 18, 1906, would present new challenges and an unexpected opportunity to confirm President Jordan’s assertion that, “it is not buildings that make a university, but professors and students.”

Two days after the earthquake, President Jordan announced Stanford University would suspend all class work for the rest of the college year. Despite hopes the term could be completed, the faculty Advisory Board concluded that damage to the campus was too extensive. University staff quickly turned to preparing the campus for the return of students and professors in the fall.

President Jordan, professors, and board of trustee members conscientiously informed alumni and the rest of the country what had happened at Stanford. They prepared articles for both local publications as well as professional journals. The May issue of The Stanford Alumnus described the damage on campus, reprinted official statements by Jordan and others, and appealed to alumni to help correct mistaken impressions about the university and its future.

The choice of Dr. David Starr Jordan as Stanford's first president had been a happy one. He had not only handled the problems of starting a new university, but had dealt with academic budgets being cut back in order for an extensive building campaign to progress, and handled a major catastrophe that had left his university in ruins. Stanford University recovered and grew strong during his 22 years as president.