|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Walking Tour

| << Previous Stop |

|

|||||||||

|

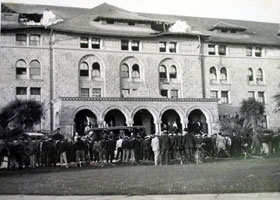

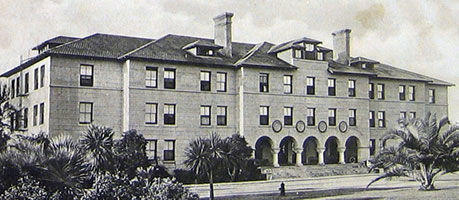

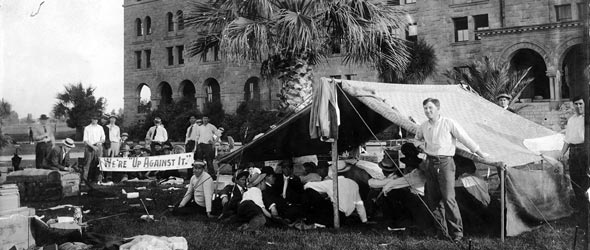

The earthquake made a lasting impression on students when it roused them from their beds at 5:12 a.m. on April 18, 1906. Stanford’s yearbook, the Quad, recounted the effect of the experience: “[T]he earthquake […] has left in our minds certain recollections which can never be effaced utterly, but will remain for years to come, rushing in upon us from time to time, even in the midst of the stress and excitement of a busy life. […] None of us will ever forget the nameless terror of the shock, the appalled astonishment with which we gazed at the ruin around us, and the sense of our own utter helplessness.” Students at the time lived in a variety of accommodations, including Encina Hall, Roble Hall, some smaller dormitories, and many fraternity and wood frame houses. Falling chimneys were the primary source of the damage to these buildings. Given the extent of the destruction throughout campus, however, the quake claimed astonishingly few casualties. One student was killed in Encina Hall, and one maintenance worker died at the University’s power plant. If the earthquake had arrived later in the day and students had been in classrooms instead of dormitories, many more lives would likely have been lost. Death at Encina Hall Figure 1: As originally constructed, Encina was one of the finest dormitories in the country. Encina Hall was the first men’s dormitory on campus. The lavish four-story sandstone structure was modeled on a resort hotel that the Stanfords had visited at Lake Silvaplana, Switzerland. Leland Stanford dedicated four-fifths of the cost of the Inner Quad to the construction of the 280,000 square foot Encina Hall, a dormitory which could accommodate up to 400 men and was counted among the finest in the country (Figure 1, 2). From the time it opened its doors in 1891, Encina was known for its frontier spirit. “Encina men were proud […] that student activities, student plans, [and] student leadership [were] centered in the Hall,” Leslie Elliot, the first registrar explained, “[b]ut this pride did not seem to include a personal feeling for the building itself. Its noble architecture, its amplitude, its great dining hall, its furnishings, were not thought of as personal possessions to be cherished and jealously cared for. Accordingly, as time went on, everything that could be abused was abused. […] Encina was […] known to outsiders as the ‘madhouse.’” Nothing could affect the rowdy disposition of this residence until, according to Registrar Elliot, the earthquake “did something to clear the local atmosphere.” One of the Stanford Daily’s headlines on the day of the quake announced “DRAMATIC SCENES IN ENCINA HALL.” Because it housed a considerable portion of the student body and was the site of the only student death, Encina Hall was central to the Stanford student’s earthquake experience in 1906. According to the Quad, “there was a terrific grinding of masonry, as of stone upon stone, for the entire height and width of the walls. The shaking of the building was so violent that it was difficult for one to keep one’s feet, and several who leaped from their beds at the first shock were thrown to the floor. Large fragments of plaster fell from the ceilings and walls, blinding and half stifling the occupants of the rooms. The ever-repeated crash of falling masonry added to the uproar. The great ornamental chimney, hurled to the roof by the shock, dashed itself through four stories to the basement, carrying with it three rooms with their five occupants. […] Practically everyone in Encina rushed half clad from this building” (Figures 3, 4). Sophomore Junius R. Hanna, of Bradford, Pennsylvania, was the only student who died in the disaster. Hanna was unable to reach the door of his room to exit before Encina’s immense ornamental chimney tumbled through its front wing. His room was one of those in the chimney’s path, and it collapsed into the basement. According to the Stanford Daily, “The cries of victims buried in the ruins of the collapsed third floor were plainly audible. The door of the main hall was battered down with a beam and 200 men began the work of rescue. Axes and ropes were brought from the firehouse, and the injured were removed from the debris one by one. Two hours elapsed before the mangled body of Hanna was dug out.” Most accounts agree that Hanna either died immediately from the impact or during the two hours before his body was uncovered, but in the very same issue, the Stanford Daily gives contrasting descriptions. Another article reported that Hanna’s “body was badly crushed, and he died soon after his removal from the wreck.” Eight other students were hospitalized for such injuries as fractures and lacerations. Seven of those students were men rescued from Encina Hall, and one was a woman who lived in Mariposa Hall. The injured students were reported as improving the following day, and most were released shortly thereafter. Figure 5: Roble Hall, the women's dorm, was designed similarly, but on a smaller scale. Reinforced concrete was used instead of masonry. Roble Hall and Other Student Housing Roble Hall was the women’s dormitory that complemented Encina Hall, the chief difference being that it was constructed more quickly and cheaply out of reinforced concrete (Figure 5), a relatively new material at the time, which was also used to construct the original Stanford Museum (Site 1). Reinforced concrete was selected because the decision to admit women for Stanford’s first year had been made too close to the University’s opening to allow for masonry construction, but as a result, the building withstood the shock relatively well. According to the Stanford Daily, no severe injuries occurred in Roble. The two front chimneys fell, causing portions of the upper floors to collapse to the first floor. Similar to the experience at Encina, three women dropped down one to two floors, but they were not buried in the wreckage and survived “without a scratch.” Damage to the building was otherwise cosmetic, consisting of broken window panes and plastering. The quake was felt most violently in wood-framed houses, some of which were pitched off of their foundations, but the situation in those houses was much less perilous than in the larger dormitories constructed of heavier materials. Damage to the frame cottages and the fraternity and sorority houses was limited for the most part to falling chimneys, wrecked plaster, broken china, and overturned furniture. One resident of a frame house that was among the worst damaged wrote, “The first shock […] forced our house four feet off from its foundations. All the doors in the house were jammed in such a manner that we were unable to leave our rooms until the disturbance ceased. […] We are now living in a tent on our tennis court, and if more shocks come, there will be nothing to fall on us.” Today, one of the most common retrofits performed on existing wood-framed structures bolts them to the foundation. Temporary Tent Cities Figure 6: Students built makeshift tent cities outside of Encina Hall in the days following the 1906 quake. The experience of living on a tennis court was not uncommon. Fearing aftershocks, the students slept outside in tents or under the stars for several days. One of the largest temporary tent cities was on the lawn in front of Encina Hall (Figure 6). The displaced students nicknamed the area of shrubbery in which many found protection “Easy Street.” A student remarked, “It was funny to see the [r]ows. People were afraid to go into the houses. On every lawn up and down the streets you could see whole fraternities of men and women sitting on rugs and pillows.” It was not until the anxiety had worn off and it began to rain on the weekend that buildings were declared safe and began to be repopulated. Many of the students had already set off for their hometowns by that time. Earthquake survivors’ intuitive fear of returning to buildings tends to safeguard them because the threat of aftershocks drops off exponentially (with time) after a large earthquake (Figures 7, 8). So, in fact, buildings do become “safer” as time passes after a quake. Student Reactions Letters, diaries, and telegrams provide detail about the experience of the earthquake from the perspectives of the students. In a letter written within hours of the earthquake, the tone with which one woman recounted the disaster is remarkable but representative of the way that some students reacted: “Dearest Folks: Strange to say, I’m still alive! I can’t tell the beginning for I don’t know anything about it, except this—I have a faint recollection of sitting up in bed (I guess it was light). Somehow I got my kimono (knocked all over the room to get it) and next found myself in Eva’s room. I don’t know how I got there, or what I thought, I never heard such a noise in all my life, and things were just flying all over my room. […] We are sitting out on the lawn now, waiting for another shock. Expect it about 11—got news from Mr. Hamilton. Good by[e], if the earth swallows us up. We’re hoping for the best and are really quite cheerful. I can’t tell you how perfectly miraculous it is that we are all alive. Not a soul in our house was even scratched.” Another student in Roble Hall described finding a friend in the middle of the parlor: “[…] I saw across the hall the third floor had caved into the second. I ran into the parlors and found Ruth just getting out of bed and shaking off the plaster. Her room had sunk right down in the middle taking her bed with it, and she wasn’t scratched. Her roommate was still up above on the third floor having hysterics and called ‘O Ruth, where are you?’ and Ruth calmly answered, ‘Down here in the parlor.’ Right above Ruth’s bed was poised a great heavy stone which had crashed through the roof and floors from the chimney, and the terrible weight is still poised there held by nobody knows what.”* As their letters indicate, the students tried to remain as lighthearted as possible. Famed philosopher William James described the phenomenon as “the good hearty animal callousness of those immediately struck.” According to the Quad, despite the devastation and loss that took place at Encina Hall, “there was no real panic, and the men, with some few exceptions, displayed remarkable coolness and judgment.” Furthermore, when the students noticed the flames on the horizon, many immediately abandoned their own worries, walked 40 miles up the train tracks to San Francisco, and joined the “Camp Stanford” relief effort. Some students remained in San Francisco throughout the summer. President Jordan later noted that the earthquake had seemed to have a sobering and maturing effect upon the student body, even the rowdy men of Encina Hall. Resumption of Work David Starr Jordan initially issued a statement in the Stanford Daily on April 18 that classes would resume the following day, and he requested that the students help the professors put their departments, laboratories, and the library back in order. It was quickly apparent, however, that campus operations could not continue before some reconstruction took place. After meeting with the Advisory Board, Jordan announced on April 19 that classes were suspended until the next academic year, which would begin as planned on August 23. Professors awarded students credits on the basis of their work prior to the quake, and students who were not in good standing took special examinations before they returned home or at the beginning of the next term. Seniors who passed were awarded diplomas, but commencement was postponed until September 15. See an image gallery of the Dormitories

|

||||||||

| << Previous Stop |